From 3 October 2019 until 12 January 2020, an exhibition at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg on amateur photography as it evolved from the Bauhaus period to the era of Instagram. Ulrike Bergermann

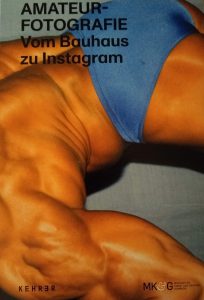

Amateur Photography: From Bauhaus to Instagram.

© 2019 Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg Berlin, authors, artists and photographers [and translators]. ISBN 978-3-86828-964-0

Translators into English: Jennifer Taylor and Alexandra Cox. Translated by Alexandra Cox: Word of Welcome; Here Comes the New Algorithm! Photo Filters and Collective Normalizations, by Ulrike Bergmann; Photographic Activism, Civil Testimony, and Collaborative Visual Politics under the Banner of Digital Connectivity, by Susanne Holsbach. Also some of the artist info and information about featured newspapers. Ulrike Bergermann

Here Comes the New Algorithm!

Photo Filters and Collective Normalizations

by Ulrike Bergermann (footnotes not included here)

To place the means of photographic production in the hands of amateurs—what an emancipatory program that was. Its realization is complete with the advent of digital media: Own a smartphone, and you have a camera; get connected and you can curate your own gallery on Instagram. When the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche opined, “our writing equipment takes part in forming our thoughts” , the influence that photography was having upon his work still appeared manageable. When a photographer asks himself or herself how the camera codetermines his or her pictures, at least viewfinder and shutter are held in his/her hand and the lens functions similarly to the eye. However, today it is up for debate whether digital components of current photography practices do not in fact ‘co-write our pictures’, over which we have no power, which are not in our hands and are not even in our cameras any longer. Whereas the Bauhaus photographer Werner Gräff, in his programmatic treatise Here Comes the New Photographer! , still called on camera manufacturers to relax technical standards in order to enable new forms of expression for professionals and other users, barely a century later the boundaries between career photographers and everybody else have faded into the background and technologies for taking photographs to a high technical standard are widespread. Above all, though, it is no longer meaningful to address digital images solely as individual objects, as Winfried Gerling, Susanne Holschbach, and Petra Löffler establish. This is because information on the location of the shot, the camera, and the chip generation, along with programs which the file will have run through once it has been edited, tagged, and uploaded to a platform, are an integral component of the image; on the platform, in turn, the photo is commented on, people are marked on it (potentially automatically), images are liked, forwarded, etc. Therefore, photography theory’s occupation is with “photographic practices” from now on, and with “photos” in the historical regard only. These practices include the activities of the people taking photographs, but also those of the technologies. Today, photography is a matter of “distributed power to take action” , the components of which are to be considered individually in each case. Everyone is able take photographs, everyone is an amateur, or an artist, or a professional—in everyone’s case, the work tools have a say as well.

The outcomes of this distribution of roles among professional producers, consumers, and others are prosumers. “Prosumers’ activities are linked with the activities of the programs” : The early form of democratizing a participative culture, in which the first generation of databases and social networks provided storage space and ordering systems, was followed by an increasing preformatting of photographic practices by the big businesses providing the platforms, as Susanne Holschbach demonstrates. For example, Instagram offers various filters and editing tools that are able to alter photos and are mostly used to ‘beautify’ the photographed persons—self-presentation is Instagram’s most common mode of use. Now, photos are displayed according to “relevance”, and what is relevant is decided by Instagram’s algorithm. For example, since March 2016 it is no longer possible to define the sorting oneself, chronologically for instance. The algorithm does the sorting, and it also does the eliminating. Wilfried Gerling has analyzed the technical fundamentals of these flexible normalizations, and points to an “authorship of millions” that arises from the use of statistical data for the forms of representation found on photography platforms.

Updating…