© 2012 Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg Berlin, © 2012 Christiane Stahl, ISBN 978-3-86828-241-2

Essay by Christiane Stahl, translated by Alexandra Cox

(the first few paragraphs – total length of the translated text: approximately 1,500 words) Click here to read the German source text.

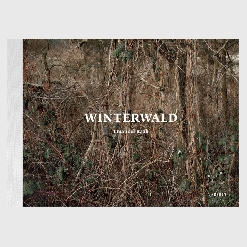

Barely a way through. Wall-like, impassable scrub towers before the beholder; major exertion would have to be applied in one’s attempt to clear a path through there. Only the eye pierces forth into a woodland located beyond. Trees, a meadow, or a pond become distinct in the background; occasionally, the evening sun-illuminated sky shines through.

It is winter, but the blackberry bushes are still bearing their leaves and the prickly branches have not yet lost their luminosity (fig. 24, cover). The late-afternoon twilight reduces colors to tender nuances of green-yellow and violet. Emanuel Raab’s quiet, almost monochrome photographic works show the multiformity of a natural space that is revealed only in the winter manifestation. The reduction of the portrayal strengthens concentration on the aesthetic design of the pictorial elements, which veer into abstraction. A tangle of wildly rampant branches and twigs conjoins to become a pattern that stretches like braiding or spider webs across the forest landscape lying behind. The graceful lines intertwine like a delicate drawing with the richly detailed surface structure; after protracted perusal, the chaos falls to order.

The slight depth of field means that only the overgrown surface is in focus: the plane behind is blurred. Repeatedly at the center of the image, a circular or ellipsoidal view is granted of the out-of-focus image plane located beyond (fig.15). What is behind remains enigmatic; the hazy glimpse shows the forest as impenetrable jungle. Curiosity is piqued and guarantees one’s perseverance in the scrub for longer. The photographs are not large-format, 45 x 60 cm including a wide white margin that defines the subject as an image construct. The image, and not its sheer size, must achieve the result that the beholder loses himself within it.

The natural space becomes planar, spatial dimension reduced to three levels. In landscape painting, the image structure made up of foreground, middle ground, and background remained essentially intact from the late Middle Ages through to Romanticism. In reminiscence of painterly composition methods, a number of images have the effect of those of a painter who smudges his painting lightly with a very soft brush, and upon that places a second coat of paint with the precise portrayal of undergrowth that stretches like a net across the space behind and shifts the vision to the image depth. It is not for nothing that the artist prints the shots on deckle-edge, not photographic, paper, as the intention is to leave open the possibility that one thinks of painting at first sight. The symmetry of the composition elements also follows the classic image structure of historical landscape painting. The detail is chosen rigorously: millimeters have the say on expression. Frequently, the pictorial elements are grouped symmetrically around a solid center in the image’s middle, whereby the line construction is stabilized and the self-contained character of the image content is stressed.