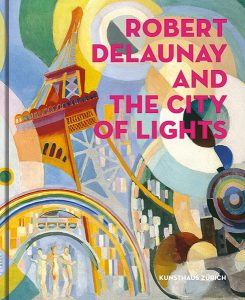

© 2018 Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft / Kunsthaus Zürich und Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg Berlin, photographers, authors, [translators!] ISBN 978-3-906269-19-1

‘The Delaunay Gang’ – The Portraits from the 1920s, by Céline Chicha-Castex

From French. Extracts

In the 1920s, Robert Delaunay made a large number of portraits: 37 oil paintings on canvas and cardboard and more than 90 drawings. The return to a form of figuration in his oeuvre has been interpreted as a break with his pre-war creation, which had been characterised by a fragmented, abstraction-tinged aesthetic. However, Delaunay had not given up figuration entirely before the war; he had introduced it in The Cardiff Team (1913), Political Drama (1914), and Homage to Blériot (1914). His major preoccupation was the prismatic decomposition of shapes under the effect of light. Delaunay had lived in Spain and Portugal from 1914 to 1921. Separated from the Parisian avant-garde artistic milieu, which had been broken apart by the war, and from his contacts with the German scene, he turned to the past masters. In Paris after the First World War, many artists sought to restore a national tradition: notwithstanding Delaunay’s criticism of this trend, he nevertheless undertook a series of fairly conventional portraits between 1922 and 1930. These works exhibit the figure and volume that may be regarded as classical concepts. How may one explain Delaunay’s being tempted, despite himself, by this return to tradition?

Prior to devoting himself to the portrait genre in the 1920s, Robert Delaunay had been approaching it from 1905 onward while conducting his initial pictorial research. The practice of self-portraiture and mutual portraits among artists was highly frequent in the academies at the time, and it was prized by the fauvist artists (Matisse, Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck). It is not a surprise to learn that he initially set out to represent his own physiognomy, making several self-portraits using a variety of techniques at the turn of the year 1905 to 1906. His draughtsmanship gains in assurance in the self-portrait of 1908: In this, he shows a certain boldness of colour, inspired by Matisse, in the representation of facial skin tones through the use of red and green tints. These tints find their response in the brown gradations on the composition’s ground, which bears abstract motifs.

[…] […]

The couple returned to Paris in the spring of 1921. […] For about ten years, Delaunay sold almost nothing. He was bewildered by the Parisian art scene, which he berated for being rather pedestrian and drawn to antique art: ‘Paris is dying out with the suffocated glory of its artists.’[i] He was critical toward artists who were participating in the ‘return to order’.[ii] By favouring nationalism, including in the cultural domain, the war had interrupted international exchanges and contributed to the resurgence of a national tradition which was turning its back on the avant-garde. In a text from 1924, ‘Constructivism and Neoclassicism’, secondary title ‘The Current Crisis in France and the World’, Delaunay laments that ‘in France, this attempt at neo-style is making itself felt most strongly among some of those who, twelve years ago, attempted a fundamental reconnaissance of art in painting’ and criticises Picasso, for ‘trying to return to the kind of classical painting that had its heyday in Italy at the time of the Renaissance’.[iii] Though Delaunay opposed this classical trend, his creation was nevertheless characterised by a return to figuration from 1915 onwards.

[i] Bernard Dorival, Robert Delaunay : 1885-1941, Paris-Brussels, Éditions Jacques Damase, 1975, p.116

[ii] Kenneth E.Silver, Vers le retour à l’ordre. L’avant-garde parisienne et la première guerre mondiale, Paris, Flammarion, 1991, pp. 130-134 (Translation: )

[iii] Robert Delaunay, texts published by Pierre Francastel, Paris, S.E.V.P.E.N., 1957, pp. 100

[…] […]

In his painted portraits, Delaunay often stylised his sitters through the medium of simultaneous coloured planes in order to suggest depth, movement and space, but these depictions remained rather lifeless. The drawn portraits are more realistic and pay homage to the poets with whom he was bound in friendship. Paradoxically, whereas the poets whom Delaunay visited were committed to a radical path, where semantic coherence is shattered, the painter returned to depicting his sitters faithfully, notwithstanding some differences of treatment depending on the techniques used. The pencil portraits of Kochno, Iliazd, Breton or Aragon, and similarly the one in wax pencil of Seuphor, pertain to a naturalist vein: the artist modulates his stroke in order to suggest the volume of the face sculpted by light. He concentrates on the sitter’s features, often leaving the torso unfinished. In the ink portraits, such as those of Tzara or Voronca, he shows greater economy of means in order to detach the characteristic features of the face; its contours are not complete, leaving the viewer to recreate them mentally. In the ink portrait of Tzara, probably preparatory to the canvas of 1923, he sums up the poet’s face in a few lines and marks. In doing so, he emphasises the monocle-framed right eye, the attribute of the poet, which one rediscovers in the portrait placed by Delaunay at the bottom of Carousel with Pigs (1922). In the context of that painting, the monocle echoes the chromatic circles of the canvas.

[…] […]