by Sabine Schimma. The third chapter in:

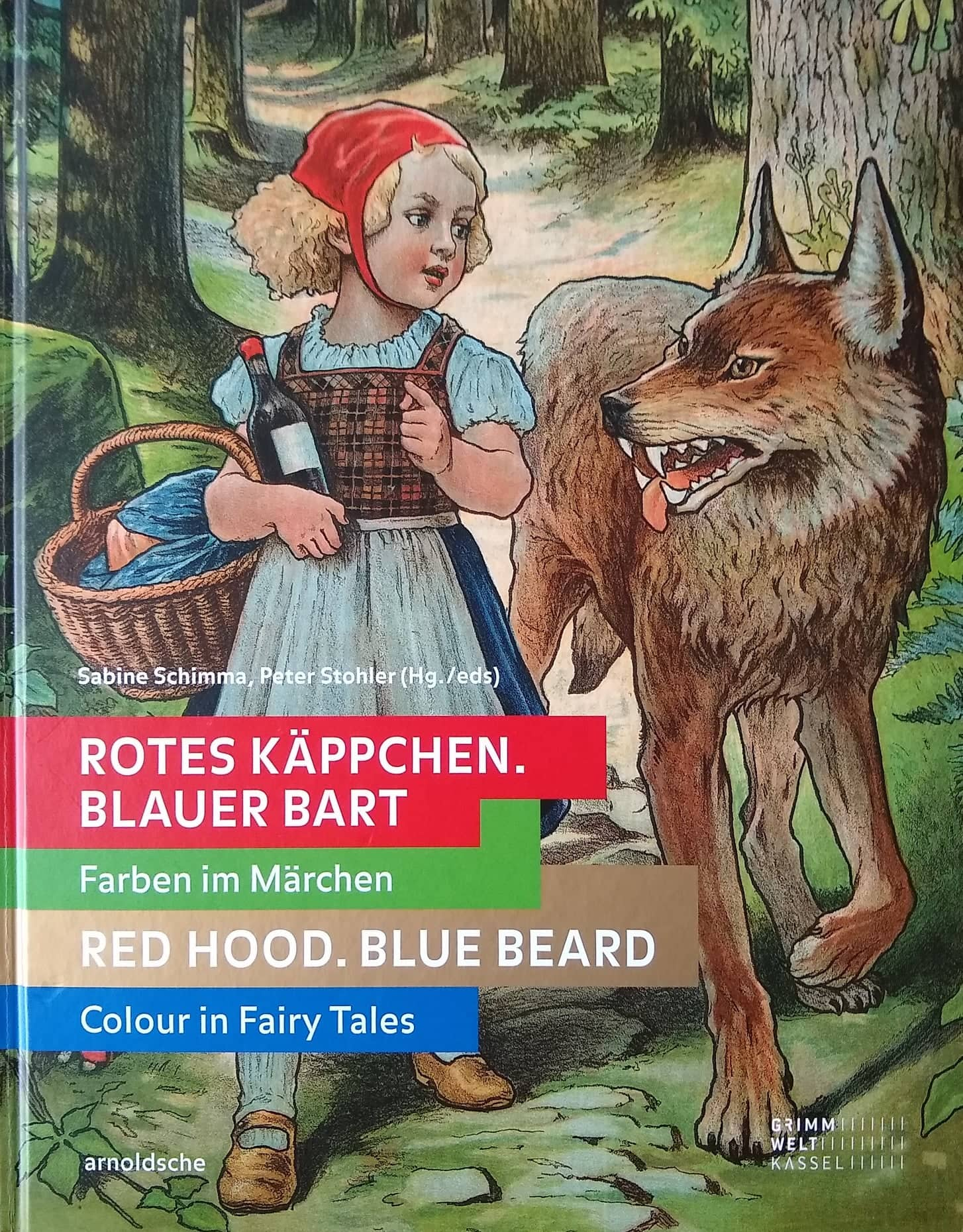

Rotes Käppchen. Blauer Bart – Farben im Märchen. Red Hood. Blue Beard – Colour in Fairy Tales

© 2019 arnoldsche Art Publishers, Stuttgart, editors/authors, translator. ISBN: 978-3-89790-573-3

(footnotes – references – removed)

Red presents itself as a highly ambivalent colour. It is traditionally comprehended as an emblem of fire and of blood and thereby stands for life and death in equal measure. As green is the symbolic colour of plant life, so red symbolises animal life. The colour is associated with health, youth and beauty in this context. Little Snow-White (GFT 53), for instance, is not buried by the dwarves because she looks ‘as if she were still living’ and has retained her ‘pretty red cheeks’. Entirely without effort, The King’s Son Who Feared Nothing (GFT 121) picks a red apple off the tree of life at a giant’s request.

In its psychological effect, red is the most energetic and most stimulating colour. It stands as a symbol of vitality and joie de vivre. In The Two Brothers (GFT 60), the city is hung ‘with red cloth’ in advance of the wedding of the king’s daughter. Behind this is the fact that red plays an important role in many wedding customs, particularly in the southern German region.

In some fairy tales, the red of joie de vivre clashes with social conventions. In Snow-White and Rose-Red (GFT 161), the latter is much livelier than her sister. She ‘[likes] better to run about in the meadows and fields seeking flowers and catching butterflies’. Not complying entirely with the passive woman’s role of that time, Rose-Red ‘merely’ gets the prince’s brother in the end, whereas the prince himself opts for the gentle and quiet Snow-White [Fig. 1)]. Vivacious Little Red-Cap (GFT 26), however, falls by the wayside entirely due to the wolf’s powers of persuasion and lands, following a detour via the bed, in his belly. In Perrault’s version, the sensuality of the little red cloak with a hood stands for the corruptibility of young girls by leering, encroaching men. Surrendering to the wolf’s lures, Little Red-Cap even lies down naked next to him. The Grimms, by contrast, highlight the consequences of children’s disobedience in defying mother’s warnings in an edifying, exemplary way. In the end, Little Red-Cap can be freed from the wolf’s innards only with the outside help of the hunter [Fig. 2]. While the Grimms do not explicitly point out the red of the head-covering, the Romantic author Ludwig Tieck, who wrote numerous fairy tales, characterises it in the first German Little Red-Cap version (1800) as the stimulating and simultaneously condemned colour of sensuality. The girl loves it because of its appealing effect; the grandmother associates it with trivial pleasures. Culture-historically, the red head-covering refers to a protective function: in many European countries, children were given red caps to wear, or were provided with other attributes of the same colour, to protect them from demons.

(…) (…)

(…) (…)

Green, the featured colour in the next chapter, represents hope and a new beginning: click on the poppy for some paragraphs:![]()

(Click here to go back to the beginning of the Red Hood. Blue Beard extracts.)