Verlag für moderne Kunst, Vienna. Contribution by Elsy Lahner, curator at the Albertina in Vienna. ©2016 Olaf Breuning, [and  translator!] ISBN 978-3-903131-47-7

translator!] ISBN 978-3-903131-47-7

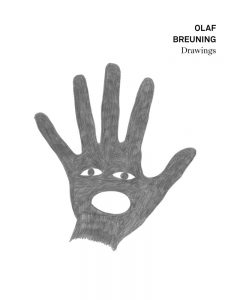

No Obstacles to Drawing, by Elsy Lahner

Extracts

The way Olaf Breuning sees it, as an artist it is almost impossible to do anything these days that no-one else has done before. Even in a globalized world, it is impracticable to be informed about everything, to know who is currently working on what and which artworks have just been made. It is therefore all the more important to Olaf Breuning to use his own unmistakeable vocabulary in everything that he does.

Olaf Breuning works with what already exists, and produces references. Consequently, his works represent translations into his vocabulary or transformations into our time. For instance, in his Marilyn series of works (2010), Breuning referred to Andy Warhol’s famous portraits of the film star, which today are among the icons of art history. For this appropriation, Olaf Breuning painted the faces of various women in vibrant colours and photographed them alone, in pairs, or in groups of four. It is fundamental, however, that he also showed the women’s bodies, which, though they blend in with the photograph’s background on account of being painted black, are clearly discernible as being naked. He thereby re-inserted a body into the portraits.

As in his other works – his films, photographs, and installations – Olaf Breuning also has recourse, in his drawing, to phenomena and media events that shape our collective experience. He showcases socially relevant themes and conflicts just as often as general knowledge from high culture and pop culture, even though these, in Olaf Breuning’s opinion, are no longer valid categories and, certainly, Pop Art specifically has played its part in blurring the boundaries between the two.

Thus, he processes gender clichés (Oh, We Men Want it All so Much!, 2005), role models (Mother Nature, 2012), and religious stereotypes (Allah is Big, 2005). He refers to Picasso’s Guernica (There is Always Someone Smiling, 2010) or Brueghel’s Baummensch (Hironiums Hosch, 2008); in other drawings, by contrast, to the latest selfie by Kim Kardashian (Please Don’t Watch, 2015), E.T. (I Hate Email, 2005), or to his observation of conversation among American girls, with their habit of constantly commentating their phrases with ‘Oh my God’ (OMG, 2013).

Some drawings are based on personal experiences, and therefore can be understood only by the initiated few; others, due to their currency, are presumably comprehensible solely in the Here and Now. The drawing Idiots, for example, which was created in 2007 and shows people standing in a row, each engrossed in their own respective mobile phone calls, might already look entirely different today, around 10 years later. Presumably, each of these same people would now be staring at the smartphones in their hands and occasionally swiping a finger across the screen. Olaf Breuning’s drawings therefore also become chronological documents, a mirror of our time.

What is further common to them, however, is the characteristic that their drawings are deliberately to be found outside the art context, too – in the case of Breuning and Shrigley, on T-shirts, textile bags and similar; with regard to Dan Perjovschi, on house walls and newspaper pages. The aim of all three is to use their statements to reach an audience beyond the vernissages, with no great inhibitions.

Olaf Breuning calls it ‘Art for everyone’, art without limits. But he is not concerned about pandering to mass taste or how much his art is liked. His chief concern is to have his works, which are produced in our time, refer directly to this time as well and, in this way, constantly challenge him to new things.

(… …)

His drawings are pointed comments on our everyday life or on up-to-the-minute events. Occasionally ironic, sharp-tongued or cynical, sometimes absurd and sometimes refreshingly banal. In their humour, but in their simplicity, too, they are not dissimilar to those of David Shrigley or even Dan Perjovschi. Shrigley and Perjovschi likewise work in a very reduced manner, monochromatically, and combine their drawings from time to time with text; nevertheless, all three artists have their own distinct style, their own signature, and the concern behind each is a different one.

(… …)