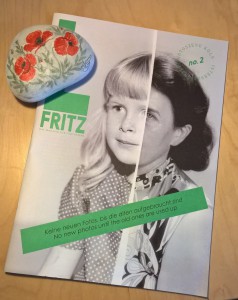

Summer 2015. Magazine named after L. Fritz Gruber distributed across Germany and Europe by Internationale Photoszene Köln. www.photoszene.de

©2015 Internationale Photoszene Köln gemeinnützige Unternehmergesellschaft (haftungsbeschränkt), photographers and authors [and translator!]

With the exception of the article by Marc Feustel, translations into English by Alexandra Cox

The first half of the Preface by Damian Zimmermann, with Heide Häusler, Inga Schneider and Nadine Preiß

From the invention of photography in 1839 until the end of 2011, an estimated 3.5 billion photos were taken – ten percent of those, however, in the previous twelve months alone. Four years later this number has risen considerably again: a billion new photos are anticipated just for 2015. With sums like these, the effect is not only dizzying – the question urges itself of what exactly the point is of taking photos when photographing has turned into something like “squirting underwater with a water pistol”, as Korean photographer Seung Woo Back has put it.

This second issue of L. Fritz, the magazine of Photoszene Köln, is therefore dedicated in particular to the artists and photographers who no longer produce their own photos, but have made it their task to view, to rate, to contextualize and to edit the existing visual material – true to Joachim Schmid’s motto, “No new photos until the old ones are used up”, they go into the archives and collections, buy photos at flea markets and on Ebay, find their images on Internet pages and in waste bins. In six portfolios, we present seven positions, (…)

©2015 Internationale Photoszene Köln gemeinnützige Unternehmergesellschaft (haftungsbeschränkt) and author [and translator!]

The first three paragraphs of Larry Sultan & Mike Mandel – Evidence, by Damian Zimmermann

It is well-known that a picture says more than a thousand words. But does a photo always speak for itself, or does it need a context in which it must be read? What do photographs tell us when we view them torn out of context? Can there ever be such as thing as a pure documentary photograph, or is not virtually every photo a document and therefore documentary photography?

Back in the 1970s, the two US artists Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel dealt critically with the perception, reality and the (incorrect) claim that photography is documentation. In the best case, a photo shows the arising of notions, but not reality, says Sultan.

For probably their most important joint work, “Evidence”, the duo, who also appeared under the label “Clatworthy Colorvues”, shot not a single photo themselves but, for two years, searched through 77 archives of a wide variety of institutes, authorities and companies such as the California Institute of Technology, a police authority, a fire department or the Highway Users Federation. Out of a total of two million black-and-white photos of experiments, equipment tests and visual documentations of damage, injuries and accidents they finally selected 59, which they published in book form. The beholder learns nothing about the images’ background and puzzles over what the annoyed-looking monkey, the men in the foam field, the plane in a hangar or footprints on a dirty tile floor have to do with one another.

(…)

©2015 Internationale Photoszene Köln gemeinnützige Unternehmergesellschaft (haftungsbeschränkt) and author [and translator!]

The first three paragraphs of The Rescued Film Project, by Damian Zimmermann

Old photo albums, discovered at some flea market, always seem to me somewhat sad, nostalgic, anachronistic. And of course very intimate. These images were never intended for my eyes. Across multiple generations, they were the visual memory of a family unknown to me.

When, then, these private archives are offered for sale somewhere, this always means, too, that somebody has parted from these albums. Because the owner has died and there are no relatives left. Because storing them seems too burdensome. Because they are not appreciated (any longer). Photographs plainly show us our own ephemerality and dispense comfort to us at the same time: some moments will outlive our physical existence and remind our descendants of us. The sale of a photo album hollows out this hope: not only have the people in the pictures died already, but so too has the beholder for whom these pictures were intended. On separation from a photo album, a family dies a second time.

However, this special intimacy is enhanced still further if I get to see private photos which neither the photographer nor the persons shown in them ever got to see themselves – even though the photos are potentially already several decades old. This is the case with the photographs of the Rescued Film Project.

(…)

©2015 Internationale Photoszene Köln gemeinnützige Unternehmergesellschaft (haftungsbeschränkt) and author [and translator!]

The first four paragraphs of Zwischen Legende und Leidenschaft – Legendary Passion “Margret – Chronik einer Affäre”, by Jule Schaffer

In May 1969 a secret liaison unfolds between “Zini” and “Schnaggel”, alias Margret S., 24, a secretary and Günter K., 39, a building materials merchant and Margret’s boss. Forty years later, a suitcase emerges containing a curious collection: hundreds of photographs, notes, fingernails – neatly archived relics of a love affair, now published in book form by Susanne Zander and Nicole Delmes.

Boss and secretary, both married to other people, seemingly the prototype of an affair – and yet, somehow, totally different: Using a typewriter, Günter K. notes every encounter with book-keeperish meticulousness and maintains an oddly sterilely obscene log of sexual intercourse on notelets and calendar pages, mentioning, for instance: “upstairs at closing time and 1x lovemaking lying on back at 5:15 p.m. – 5:30 p.m.” Obsessively he collects restaurant receipts, keeps Margret’s fingernails in blue envelopes, and sticks a bloodied handkerchief with scab and “Original hair from Margret from the GM on 10.11.1970” on an index card.

And photographs, again and again: Margret in black-and-white outside a spa hotel, Margret in colour in bed, smoking, Margret in a bra, hair back-combed, Margret in the Opel Kapitän, Margret, putting on make-up, in the green “suede miniskirt”, dressing, undressing and getting changed. In the course of time Margret’s character undergoes a transformation before the camera; she becomes more self-confident, poses on the bed and in front of the brocade wallpaper in the little love nest, which is probably located over the building materials business in Cologne. We see Günter, on the other hand, only in the bleed or as a reflection in the mirror, never whole.

The notes reveal an affair that is many-layered. Günter and Margret eat “beef pot roast”, watch “colour television” and stay in spa hotels; he checks her period (noting the time) and collects the empty pill packages. Margret nevertheless falls pregnant, has an abortion; two days later, we are off to the ball. Margret’s husband Lothar must not find out. Günter meets other women.

(…)

©2015 Internationale Photoszene Köln gemeinnützige Unternehmergesellschaft (haftungsbeschränkt) and author [and translator!]

The first three interview questions from Selling the Archive’s Soul: Meida scientist Wolfgang Ernst interviewed by Damian Zimmermann

What do you mean when you talk about the “already obsolete archive concept” and the “new archives”?

The wider archive concept is the administrative, scientific archive concept. Unlike document collections, there are firm rules with archives on what type of documents land in this memory called “archive”. For example, with state-funded film productions it’s mandatory to deliver a copy to the German federal film archive – in contrast to the library or collection, which are free to decide. Not every memory, not every depository is automatically an archive at the same time. However, in linguistic usage in the last ten years, so much archive culture has been researched that the concept “archive” is applied to almost every type of memory. The difference between free collections and archives with firm rules is blurred now.

It got even more complicated after Michel Foucault introduced the concept of “archive” as well. However, he uses it more with Immanuel Kant in mind: “What is the technical or administrative requirement of the possibility of something?” And the “new archives”, in order to introduce the third archive concept now, these are the archives that are growing up in the digital space.

These “new archives” enable a new type of archiving. So far we’ve been tagging photos, so squeezing a visual medium into a system that was actually meant for text media. How does the computer look at images?

The technical image isn’t actually an image any more, but a hexadecimal value. The image suddenly becomes a radical mathematical matrix, of which every single aspect then becomes manipulable. Only a human can comprehend it as an image. That’s probably what’s hardest for us. We still call the digital image a digital image, but actually, to be consistent, we’d have to say: the “mathematical projection called image”, or something. The computer now suddenly sees patterns and tonal values, and is able to sort millions of images according to tonal values, statistical distributions, transition probabilities or information versus disarray. We’re only gradually starting to use categories such as entropy or probability as cultural tools for memory and for trawling through images. We’re still having difficulties with that. We’ve still got the old, culture history concept of image and the new possibilities simultaneously. We need to get into the perspective of algorithms a bit, in order to discover that we can make a meaning out of that which is more than just technical management.

Can a computer see what is depicted?

The computer really does quite radically see what’s depicted – so colours and brightness distributions – whereas we humans immediately spatialize the two-dimensionality of objects in the image and see them in context. Even with very poor image quality and even when there is only a hint we grasp what’s going on there straight away, because we add to the image with our imagination and our own memory. The computer is interested in things like, for example, well-formed geometric objects being shown rather than background noise. At first glance that’s banal, but it’s of interest if we say, “Can we distinguish the style of modern, abstract art from the rather iconic art of the 19th century?”

Only a gaze like this can make concepts such as style identifiable, because it goes beyond the individual object. So, nothing is taken away from us as beholder at the same time.

(…)

©2015 Internationale Photoszene Köln gemeinnützige Unternehmergesellschaft (haftungsbeschränkt) and author [and translator!]

The final extract: the first four paragraphs of To the End of All Days, by Julius Tambornino

In 1977 NASA sent two gold-plated data carriers featuring noises, music and 115 image files on an almost infinite journey into space on board the space probes Voyager I and Voyager II. In 2012, the artist Trevor Paglen responded to this with his Last Pictures. A comparison by Julius Tambornino.

The mass of images that our humanity produces must seem well-nigh infinite to us. And as it is, in fact, impossible to indicate an exact figure, the abstract term “infinitely many” probably comes pretty close. What, on the other hand, an image actually is, and whether it is ultimately in a position to uncouple physical reality from the temporal component of its existence, is, even after centuries, one of the most intriguing questions in art and its adjacent sciences. Even at the end of the 1970s, long before image production saw exponential growth, this interpretation led to a crazy archiving idea whose realization is now racing through space at the edge of our solar system: before, in 1977, the two space probes Voyager I and Voyager II set off on their space mission which continues to this day, a gold-plated copper disc was attached to each of their outer walls and went down in history under the description “Voyager Golden Record”. Recorded on them, alongside greetings in our planet’s 55 most important languages, are noises, music and, not least, a compendium of 115 image files.

The idea behind this mysterious baggage was to convey to a potential alien species an image of us humans on Planet Earth, should the probes fall into the hands of intelligent life on their ultimately unpredictable journey. It’s hard to believe, but this oddball project, which at first glance combines naiveté and megalomania in the strangest way, was the brainchild of a thoroughly respected astrophysicist by the name of Carl Sagan. In order to understand why an occupational rationalist allowed himself to get caught up in such a thing, it is important to realize that the Voyager mission planned for a hitherto unique trajectory: after the scheduled passing of Jupiter and Saturn, in 2012 Voyager I left our solar system as the first man-made object to do so and entered into interstellar space. Though the probability of a space encounter may still be very slight with an estimated lifespan of 500 million years, it can’t be completely ruled out. And precisely this point is determinative for retroactive appraisal and enduring fascination with a thing which is, de facto, getting further and further away from us.

Another question is even more important, though: What sorts of images does this mini archive actually contain?

Of course, the most interesting aspect of this conceptual art disguised as state-backed science is not flying through the universe decades away, but arises in the human mind: due to this record’s mirror effect and in the insight which an operation like this delivers about our own cultural will.

(…)

©2015 Internationale Photoszene Köln gemeinnützige Unternehmergesellschaft (haftungsbeschränkt) and author [and translator!]