by Sabine Schimma. The seventh chapter in:

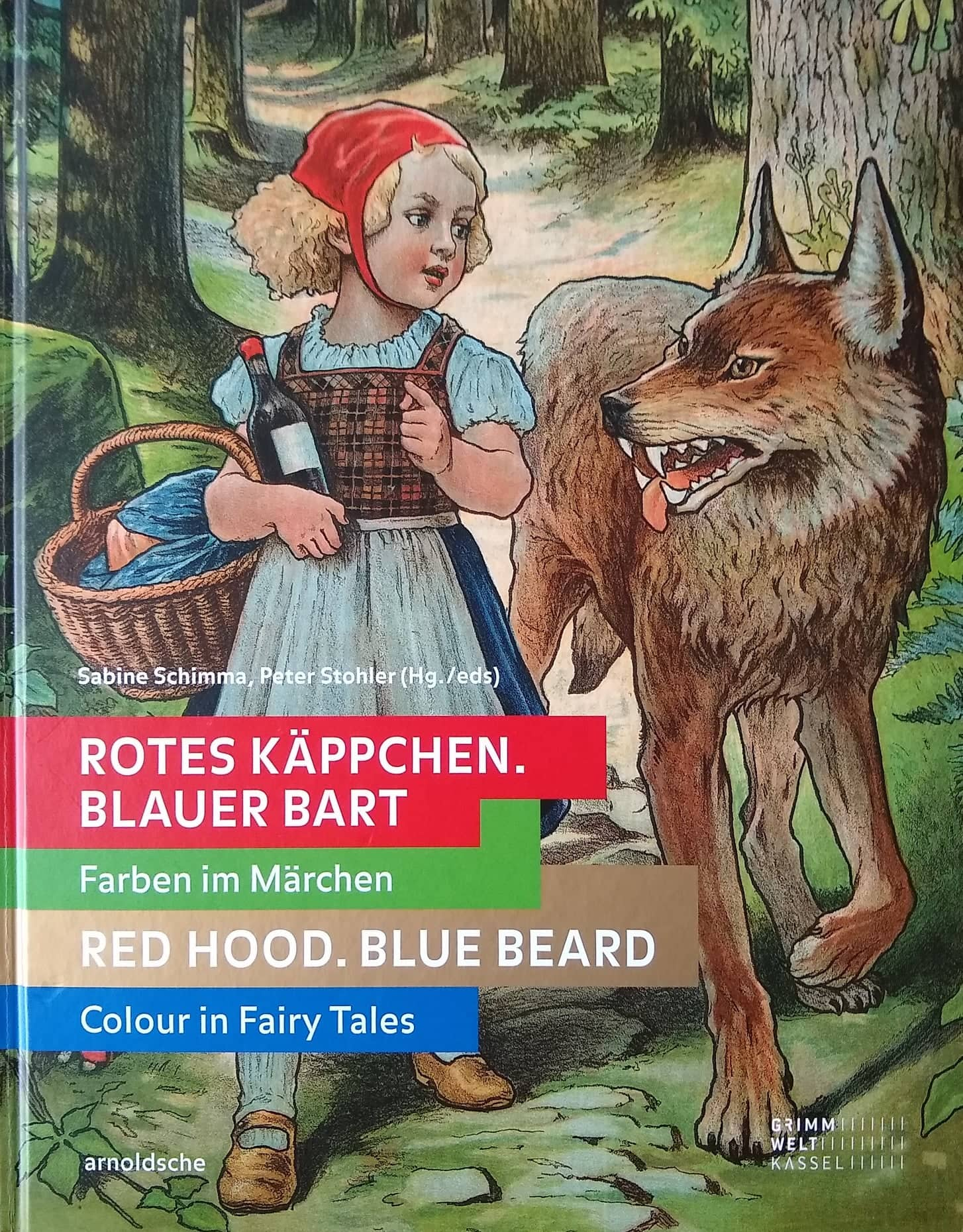

Rotes Käppchen. Blauer Bart – Farben im Märchen. Red Hood. Blue Beard – Colour in Fairy Tales

© 2019 arnoldsche Art Publishers, Stuttgart, editors/authors, translator. ISBN: 978-3-89790-573-3

(footnotes – references – removed)

Grey is the colour of inconspicuousness and uncertainty. It is deemed a vague colour, devoid of character. White is dirtied by it, black lessened in its force. It clouds all chromatic colours likewise. It also symbolises such emotions as worry and silent pain and, as the colour of misery, steals joie de vivre. A person who is worried can get grey hair. Grey is a symbol of the crepuscular. In fairy tales, the eerie figures and spirits that are able to generate disquieting feelings take on the colour – sometimes with a positive outcome. In The Golden Goose (GFT 64), a little magical grey man puts three boys’ readiness to assist to the test. He rewards the youngest, with the good heart, with the golden-feathered creature. The devil to whom Peter Schlemihl sells his shadow, in Adelbert von Chamisso’s eponymous tale, appears in the form of a shady, little grey man. In the fairy tale The Riddle (GFT 22), a king’s daughter promises to marry the suitor whose riddle she cannot solve; otherwise, suitors will be put to death. When she is unable to solve the riddle of the fairy tale’s hero, a prince, she attempts to listen to him as he dreams, in order to get to the bottom of the mystery. During this listening-in operation, she wears a ‘misty-grey mantle’.

Grey is deemed equally to be the colour of age and ageing and carries this meaning in fairy tales too. In The Hut in the Forest (GFT 169), ‘a grey-haired old man’ sits at a table; he is a bewitched prince. He is released from this spell by the goodness and industriousness of the youngest daughter of an old wood-cutter. In The Glass Coffin (GFT 163), the poor tailor is likewise received in a house in the forest by a grey little old man, who subsequently, however, turns out to be an evil magician. In The Crystal Ball (GFT 197), the bewitched king’s daughter has ‘an ashen-grey face’.

In former times, grey, alongside brown and blue, was the preferred clothing colour of the poor. Grey clothing – like brown – was worn undyed and was hence cheaper to make than dyed apparel. It was possible to produce a dirty dark blue on unbleached wool or unbleached flax through the use of woad, which was abundantly available in Europe. Furthermore, there were pragmatic reasons for using these colours: dark clothing does not appear to get dirty so quickly while its wearer is labouring. With this in mind, Charlemagne ordered peasants to wear clothing made of grey fabric. Certain fabric colours were prescribed in clothing ordinances in accordance with the social hierarchy. Poor people, orphans and prisoners wore grey clothing and thereby exhibited poverty and misery in their different facets. In the voluntarily elected poverty of Christian orders, grey, alongside brown, was deemed to be the colour of humility, modesty and unworldly self-denial, among the Capuchins and the Cistercians, for example. Here, the colour demonstrates the creation of a collective identity and of a social body outside worldly society.

In various fairy tales, grey as a clothing colour symbolises the socially disadvantaged status of the individual figure wearing it, since colour determines a figure’s identity. At the same time, it marks the existence of a temporary state, of a time-limited ‘grey area’, which is about to change through the self-initiative of the protagonists. They are obliged to do hard work in the kitchen and throughout the household, to which they are condemned by wicked stepmothers. Stepmother and stepsisters take Cinderella’s (GFT 21) ‘pretty clothes away from her, [put] an old grey bedgown on her, and [give] her wooden shoes’. She has no bed, but is obliged to sleep next to the hearth in the ashes – in the kitchen, the innermost place in the house [Fig. 1]. Cinderella gets her name because she always appears ‘dusty and dirty’. With this look the dust of oblivion and invisibility symbolically clings to her, for, with the clothing and tasks of a servant, the girl is situated on the lowest hierarchical level in society and family at once. Her name has now become the winged word for publicly unnoticed work in the home, which is still deemed to be a typically female domain.

Unlike Cinderella, who works chiefly in the house, Allerleirauh (GFT 65) breaches the latter’s boundaries and chooses her social status herself – driven to do so out of necessity, mind you, since her father seeks to marry her. Wrapped in a patchwork mantle of all kinds of furs, she flees the paternal palace with three magnificent dresses concealed in a hazelnut, her face and hands coloured black. She, too, is not spared sweeping the hearth and other arduous household tasks, though she performs them in a royal palace. As a place to live she gets a closet under the stairs, into which no daylight falls. Here, too, the principal figure lives in a zone of the not-visible. Wrapped not in a mantle of animal pelts, but entirely in a beloved donkey’s grey skin, flees princess Donkeyskin, in Charles Perrault’s fairy tale of the same name. She actively endeavours to find employment herself and, after several failed attempts and life as a vagrant, enters into service as a scullery maid on a feudal estate. Here she tends sheep and goats and cleans the pigsties, is obliged to live in the most hidden-away corner of the house, and is mocked by the attendants at first, since she looks so ‘dirty and repellent’. In Hans Christian Andersen’s The Princess and the Swineherd, a poor prince likewise elects his destiny as a ‘Cinderella’ himself, since the emperor’s daughter has spurned him. He wraps himself in poor garments, colours his face black and brown and enters into service as an imperial swineherd, in order to have his revenge on her. He presents her with wondrous inventions, which she absolutely has to possess herself, so that she even rewards him, the dirty fellow, with the kisses demanded in return [Fig. 2]. He is given a ‘wretched little chamber’ down by the pig shed. (… …)

(…) (…)

(…) (…)

The book’s eighth and final chapter is ‘multi-coloured’: the poppy leads to the final extracts here from Red Hood. Blue Beard:![]()

(Click here to go back to the beginning of the Red Hood. Blue Beard extracts.)