by Sabine Schimma. The fifth chapter in:

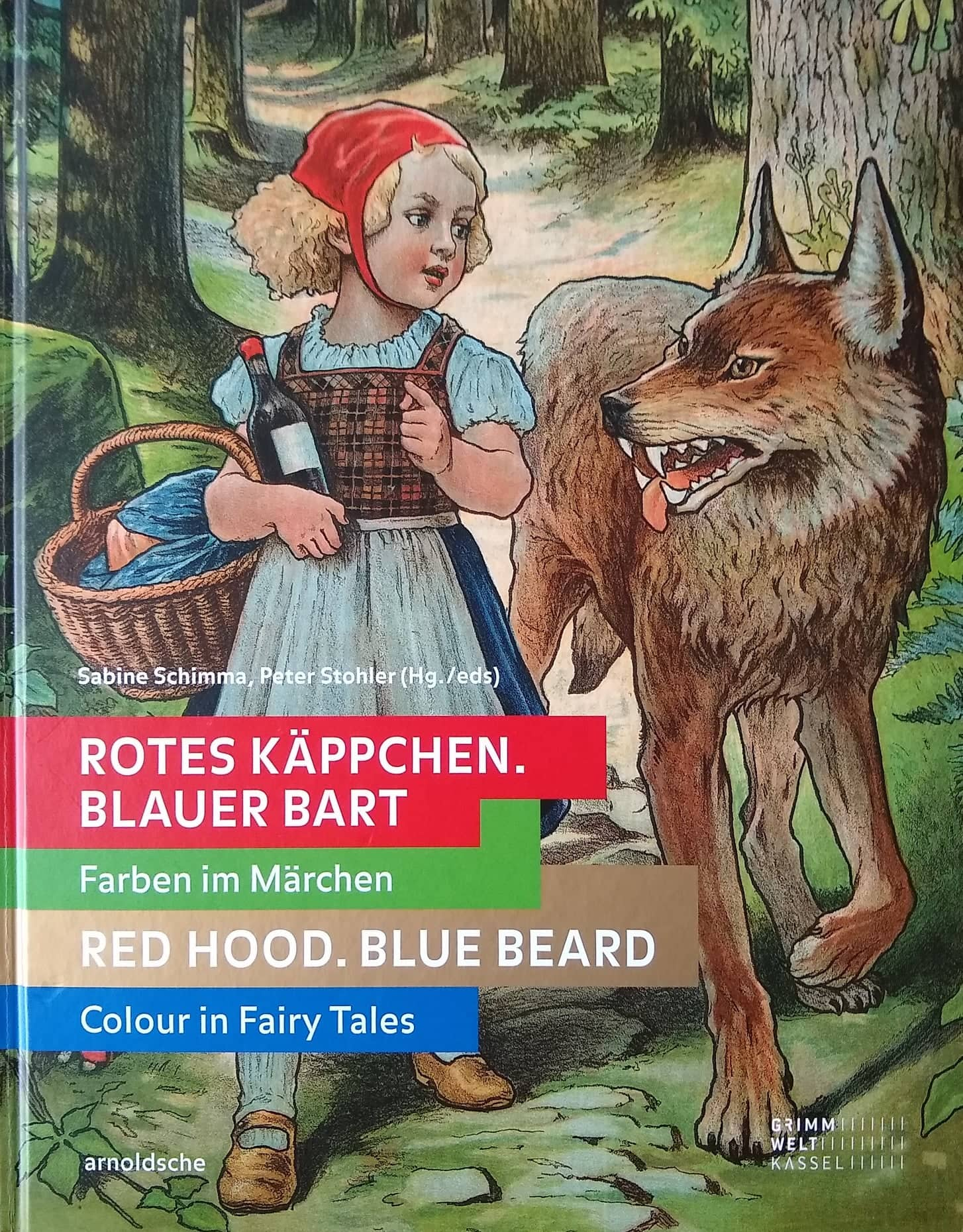

Rotes Käppchen. Blauer Bart – Farben im Märchen. Red Hood. Blue Beard – Colour in Fairy Tales

© 2019 arnoldsche Art Publishers, Stuttgart, editors/authors, translator. ISBN: 978-3-89790-573-3

(footnotes – references – removed)

Blue is regarded as the colour of the infinite and remote. It creates distances and seems to withdraw itself from man. The further away an object is outdoors, the more bluish it appears through the atmospheric strata. For example, The Drummer (GFT 193) in the fairy tale descries, ‘in the blue distance’, the glass mountain, in which the king’s daughter is being held captive by a witch, who is to be vanquished.

Blue symbolises the transcendent and abolishes boundaries, by which means it refers to freedom and uncertainty at the same time. The colour exhibits its effect in removing limitation, particularly in the blue of the sky and the ocean. For example, the girl in The Twelve Brothers (GFT 9) and the king in The Girl without Hands (GFT 31) go ‘as far as the sky is blue’ in order to help their loved ones.

Closely associated with the symbolism of water, blue stands for mental profundity, the intellectual, and also the unconscious. The Little Mermaid by Hans Christian Andersen is an eloquent example of this: as the most beautiful of six sisters, she has eyes ‘as blue as the deepest sea’ and lives far out in the ocean, where the water is as blue ‘as the petals of the loveliest cornflower’. Even the sand of the seabed is blue, and above the realm of the merfolk lies ‘a wonderful blue sheen’ which recalls the sky rather than the ocean’s bottom [Fig. 1].

The mermaid falls in love with a prince whom she saves from drowning. She becomes a human for his sake by exchanging her fish’s tail for two legs [Fig. 2] and venturing the hazardous risk of dying if her love is not reciprocated. The worst happens, and she must give up her life. In emotional verbal images, the blue in this fairy tale refers to an unfulfilled love, an unsatisfied longing.

Probably the best-known symbol of longing is a blue flower, which constitutes the initial and simultaneously key scene in Novalis’s Heinrich von Ofterdingen, which retains the format of a fragment novel to the end. This novel goes on to become so strongly condensed in its progress – due to the tales, dreams, songs and conversations inserted into it – that it ultimately transitions into a fairy tale. Heinrich, having reached a cave and swum through a pool to the other shore in his dream, experiences the following vision: ‘However, what attracted him with full force was a tall light-blue flower, which stood beside the source and touched him with its wide, gleaming petals. […] He saw nothing but the blue flower, and contemplated it for a long time with a tenderness that cannot be named.’ When he tries to approach the flower, its petals move and reveal a gentle visage. It is that of his subsequent beloved and wife, Mathilde. This flower does not present itself as an objective thing of nature, but changes with the observer himself. Subject and object blur, man and nature coalesce into one unit, which becomes visible only in the medium of the dream. The blue flower becomes an emblem of the blue of the endless sky and lends its symbolism to an entire era: Romanticism. Romanticism signifies the abolition of boundaries in a dematerialised, dreamlike nature that points beyond reality, the indistinguishability of this life and the afterlife. The blue flower stands equally for aspiration towards both individuality and self-knowledge, which simultaneously becomes a knowledge of nature. Its real-life models are seen in cornflower or chicory – Novalis himself refers to a blue heliotrope.

(…) (…)

(…) (…)

Gold and Silver follow on from Blue. Click on the poppy to read some of those paragraphs:![]()

(Click here to go back to the beginning of the Red Hood. Blue Beard extracts.)