© 2015 Museum Tinguely Basel, ZEIT Kunstverlag GmbH & Co KG, authors,  translator, artists.

translator, artists.

Editorial, by Roland Wetzel, Director Museum Tinguely

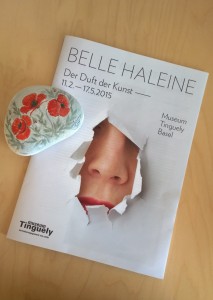

“Belle Haleine. The Scent of Art” is an experimental exhibition that shines a light on the fascinating world of odor and olfactory art. The “beautiful breath” of the title refers to an artwork by Marcel Duchamp, an assisted readymade that developed from a famous perfume (perfume flacon) from the company Rigaud of 1921. Its substituted label is adorned with Duchamp’s portrait of his female alter ego “Rrose Sélavy” – Eros as the focus of life – and is inscribed with “eau de voilette” – the water of a little veil.

Certainly, our olfactory brain is susceptible to deceptions; just think of the food industry’s methods or scent identities conveyed through marketing, or – as concerns desire – our endeavor to appear in the best olfactory light by using perfume. Simultaneously, though, the nasal sense is one of the most direct, one of the most archaic senses; it is not in thrall to the will but links directly with emotions, and awakens memories and associations that seem far removed from reason.

The sense of smell is not represented in our increasingly digitalized life worlds (yet). In research, the universe of smelling still harbors much that is unknown, and so, with its anarchic force as a component of artistic works, it is perhaps of particular interest precisely today.

This booklet is the extended version of a WELTKUNST supplement to DIE ZEIT that was published on the topic of odor in art. In the present version it additionally contains a plan of the exhibition at Museum Tinguely, information on the individual works, which date from the 16th century through to the immediate present day, and a supporting program, which extends from a Pheromone Party (14.2) to a broadly based scientific symposium (17.4-18.4).

Laissez-vous embaumer!

The first paragraphs of ART FOR THE NOSE, page 5 of the Belle Haleine magazine:

“But, when nothing subsists of an old past, after the death of people, after the destruction of things, alone, frailer but more enduring, more immaterial, more persistent, more faithful, smell and taste still remain for a long time, like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, on the ruin of all the rest, bearing without giving way, on their almost impalpable droplet, the immense edifice of memory.”

Such is Marcel Proust’s summary, in his great novel “In Search of Lost Time,” of the famous madeleine episode, when a cake dunked in linden blossom tea sweeps the first-person narrator into a rapture that culminates in a spontaneous journey back to the past. Here, Proust has smell appear as taste’s twin brother, and rightly so – after all, both of them, as chemical senses, represent the phylogenetically oldest sensory system. Silk moths and even microscopic animals that inhabit our slippers benefit from it. That is, smell is a “remote sense”: it warns the organism of imminent danger, but it also – when lured by aroma – draws attention to abundant sources of food or potential mates.

In humans, the sense of smell additionally takes on another important role. It is our unconscious memory prop, the most competent archivist of memory – as Proust already sensed and as neurological research, in recent years, has impressively confirmed: In the so-called piriform cortex of the brain, olfactory impressions are memorized so that they can be retrieved later and immediately in similar situations. Based on minuscule*, familiar signs, experienced episodes are recalled in milliseconds: Stone Age man recalls his unpleasant encounter with a lion, or the French literary genius his idyllic childhood in Combray. In evolutionary terms, our memory came about as olfactory memory; ergo, it associates memories with positive or negative assessments. This is what makes olfactory perception appear so varied in modern man: emotions and associations are individually tuned.**

This fact also fascinates contemporary artists, who conjure up Proust’s “almost impalpable droplets” in their works in order to arrive at certain remembered stories, clichés, or prejudices. …continues…

* I had used “tiny”: that has been altered in the magazine to the misspelled “miniscule”!

** My original translation (in keeping with the German): depending on one’s cultural conditioning, scents can evoke completely different emotions and associations in every individual.

These, and other tiny alterations in this text, are very very minor and are absolutely acceptable, but the plea to consult the translator when changes are significant stands.