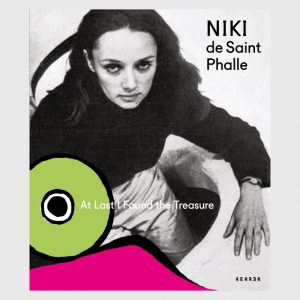

Niki de Saint Phalle. At Last I Found the Treasure ©2016 Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg Berlin, Kunst- und Kulturstiftung Opelvillen Rüsselsheim and authors [and translators!] ISBN 978-3-86828-720-2 Niki de Saint Phalle Beate Kemfert

(… …)  Beate Kemfert

Beate Kemfert

While searching for new forms, in 1965/66 Petit developed the idea of choreographing a ballet based on Erasmus of Rotterdam’s (1469–1536) L’Éloge de la folie (original Latin title: Laus Stultitiae, Eng. Praise of Madness). He asked his friend, the author and journalist – and former secretary of Jean-Paul Sartre – Jean Cau (1925–1993) to write the libretto. Cau, born one year after Petit, agreed: ‘We wanted to pillory all the evils of the modern age.’

Only the title was borrowed from Erasmus. The aim was to create a contemporary ballet, ‘made in 1966’, in which modern follies were to be visualised and made tangible, not only through dance. As the elaborately designed, collage-style programme (fig. p. 65) demonstrates, the visual artists de Saint Phalle, Raysse, and Tinguely not only designed stage sets and costumes in the classic sense, but also brought in their ideas and images, which became part of the overall concept. (… …) Cau explained the contexts in the accompanying programme. According to his remarks, the dancers were to dance ‘praise of madness’, which, like life and the world in general, is full of contrasts. (… …) Beate Kemfert

Although there were frictions between the artists and Petit during the realisation, according to de Saint Phalle the joint project amounted to genuine collaboration. It was, she said, teamwork from the start, both with the three stage designers and the three artists, as well as with Roland Petit and Jean Cau, along with Maurice Constant. To the artist, this collaboration was the most interesting aspect. Additionally, impresario Petit hired new dancers in order to realise the intended synthesis of music, dance, colours, and shapes. A costly enterprise was born; in the end, Petit was forced to tap into new money flows in order to fund it. Even the stage curtain for the overture was monumental. Tinguely designed a 3.5 x 6-metre-large relief sculpture, which could be moved and raised up through the treading of built-in bicycle pedals. The mechanical construction, comprised of aluminium painted black, wooden wheels, and drive belts, functioned like a shadow play. The relief was built behind a white, illuminated surface, and the silhouette of the dancer treading the bicycle pedals during the performances was a component of the work as well. As soon as the curtain had been set in motion, balls rolled down the inside of the sculpture, chutes tipped, and – to mark the close – a guillotine fell. Raysse, who was responsible for the colours, designed the second, third, and eighth scenes no less elaborately. For ‘La Publicité’, he realised a giant image of a woman’s face, which was drawn in neon lights. He introduced his favourite décor of palm trees, sun, waves, and blue sky to ‘L’Interrogatoire’ as mock architecture. The dancer unfolded the décor by opening the palm tree and switching on the moon. For the act that depicts love, the artist chose the Metro as the stage set: between a reflective ceiling, a fluorescent orange-coloured floor, and a wall of chromed steel, two dancers dressed in orange were tied to a vertical pole. Niki de Saint Phalle

Niki de Saint Phalle designed the fourth, fifth, and sixth acts of the nine-part ballet, as well as the poster, plus the cover and an inside page of the programme (fig. p. 65). For the act ‘La Femme au pouvoir’ (Power to the Woman), she developed six fully sculptural Nana figures in different colours and shapes. De Saint Phalle also used the opportunity to realise her ideas for the stage on a large scale and created a pregnant Nana and dancing figurines (fig.p. 64), which were larger than the dancers holding them, along with an oversized Nana with a handbag. ‘The garishly painted, giant foam-rubber dolls’, with their broad hips that moved delicately to sounds of Chopin as ‘coarse symbols of the feminine’, alienated some reviewers from the German press. The first five Nanas appeared on the stage in a dark, black area, arranged in a circle and brightly lit (fig.pp. 62 / 63). The film of the same name, produced by Petit in 1966, records the stage choreography of the voluptuous Nanas, which are carried and held by five male dancers in grey tights and black leotards. Each of the men rotated one of the five oversized Nanas slowly and varyingly in time to the music. (… …) The Nana in the black-and-white ballet costume bearing the text ‘MOI’ stood on one leg. The other leg was bent backwards and the arms were swung forwards and backwards. With a sweeping gesture, the male dancer invited her to dance and encircled her until he was carrying the ballet-Nana across the stage. As he walked, the other dancers continued to move their figurines. Once ‘MOI’ had arrived back at her position, all Nanas were raised up. While four Nanas were brought together as one group, ‘MOI’, also still raised up, moved solitarily. Raysse comments on this as follows: ‘The dancers carry parts of the female figures. Breasts, buttocks, or a knee made out of particularly light plastic. They dance and ultimately unite in order to form one giant woman. That is woman as she is seen by woman, the opposite of the male dream, of the immobile, ecstatic, consenting woman. It is female flesh, overrunning the world.’ At the close of the act, with an abrupt shift from the Chopin suites to shrill electronic music, a larger, multi-coloured Nana in a flowery dress with a black handbag and red high-heeled shoes was lowered onto the stage from above and appeared to crush the male dancers. The men first stretched out their arms to her, then prostrated themselves underneath her. With a loud closing chord, a giant Nana stood on the stage. Beate Kemfert

While the German press was a little muted in its reaction to de Saint Phalle’s ballet scenography, in Paris the ballet’s success was declared on account of the newly created decorations in particular. The monumental stage set for the act ‘La Guerre’ by de Saint Phalle had a large share in the positive reviews. In order to translate the horror of war, de Saint Phalle developed a stage set with a red backdrop and floor, along with large dragons on the left and right-hand edge and a sun in the middle (fig.p. 68). During the performance, six female dancers in white robes stood beneath the sun; men in grey tights, black leotards, and black balaclavas marched up. These male dancers formed a choreographed firing squad, and aimed gesturally at the women (interpreted as ‘Greek goddesses’ or ‘innocent priestesses’), who were ‘tack – tack – tack – mown down’ in time with the music and fell down, one after the other. The final shot hit a white sculpture of a woman standing at the end of the row of women, a variation on the Venus di Milo, out of whose abdomen paint then ran.

(… …) Niki de Saint Phalle Beate Kemfert

More Niki de Saint Phalle: The Construction of Boston, 1962, by Beate Kemfert