©2016 Internationale Photoszene Köln gemeinnützige Unternehmergesellschaft (haftungsbeschränkt) i.G., photographers and authors [and translators]

Radfahrer, by Damian Zimmermann

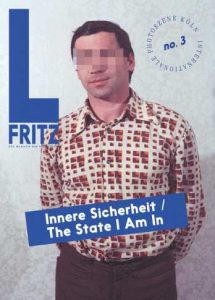

Harald Hauswald, photographer and co-founder of the Ostkreuz agency, was under observation by GDR State Security for years on account of his allegedly “hostile and negative acts”. For his film “Radfahrer”, Marc Thümmler has confronted photographs by Hauswald with extracts read off-camera from the latter’s Stasi file. In addition to the oppressive feeling of powerlessness that comes with being followed and spied on, as a citizen, by the state power at every turn, the film conveys absurdly comic moments: When a Stasi spy starts very skilfully analysing Hauswald’s black-and-white photographs of everyday life in East Berlin and subjecting them to ideologically tinted “art criticism”, this lays bare the system’s whole paranoia. (dz)

Extracts from Harald Hauswald’s Stasi file:

According to the appraisal of the IM, the visual representation is triste, without, however, fundamentally pessimistic statement. Some of the works exhibit good gift for observation. Ostensibly the exhibited works show scepticism towards the life in the GDR depicted in the photos.

- H. attempts to use photographs to create so-called “authentic” documents on the subject of the politics of party and state being directed against the interests of the people and the socialist reality of the GDR being characterized by militaristic acts, alternative ways of life and the breach of human rights.

Appraisal of “Ostberlin – Die andere Seite einer Stadt”: The photos have been selected so as to support the written statements. In their composition the photos convey a biased, extremely distorting image of the capital city, even more than that a counter-image, carefully designed not to raise in the beholder the impression that this city could be worth loving, that it could be worth living in it, that its citizens could feel at ease in it. The image selection in particular betrays that this is a book a long time in the planning. It represents a compilation of whatever could be found or used in terms of gloomy, oppressive and squalid milieu, of the most primitive. Evidently there was also a conscious decision to dispense with colour motifs, because exclusively black-and-white reproduction underlines the alleged greyness, desolateness and tristesse of East Berlin reality. In order to emphasize the everyday greyness, bleak, poorly-lit milieu was chiefly preferred, or respectively such an effect was produced during the development process. In the inner section, following a panorama and four more photos featuring the television tower as a motif from various perspectives, there is immersion straight into East German everyday life: three grouchy-looking passengers in a mode of public transport; lines of buyers in Karl-Liebknecht-Straße; police checks (see police state GDR); old woman looking for useful things in the waste bin; snack bar next to the dirty waste bin. Now in the required mood, the beholder then gets further typical motifs put in front of him. Seedy, almost empty streets and house fronts abound on page 63. In addition to these a picture of a childless playground. Where are the children? Now and then one sees some in other photos, even in larger amounts a few times. But to make sure these motifs do not stick too much: on page 161 for example a big, bleak, uncleaned house wall. In front of it, playing lonely in the dirt: a child. East Berlin slum. The more desolate, the better. What does one photograph when one is in the Pionierpark? The Palace? Or the railway? Or something else interesting? No, why is there a presently neglected open-air stage in the end? That is typical of the ever-present decay in East Berlin, after all.

Preferred motif: skinheads or other things from “the scene”. He thought them so attractive that they got illustrated by the half-dozen in large format. Anyone who, like Hauswald, demonstrates their inner attitude to solidarity in such a personal way can earn their pennies honestly – in West.

In Hauswald’s typical way of looking at things the photos are meant to reflect the isolation and forlornness of people in the everyday grey GDR. A person feels small and abandoned in a supremacy of concrete, labour, traffic and other things. Alleged contradictions between people and state power are constructed through deliberately isolated, delimitative depiction of police and army in the streetscape. Hauswald tries to depict that everything to do with the state is alien and indifferent to the person. Following appraisal of the sources, the photos and the exhibition overall have no openly discernible or conceptually intended hostile statement.

In their pessimistically gloomy statement, the newly added images fit the other ones; among them are some of the subtly taken motifs. Example: shot of a group of flag-bearers and the close of the May demonstration in 1987, where a storm famously came unannounced. Hauswald caught exactly the moment where a split-off group of flag-bearers is whirled apart by rain and wind. Flagpoles all over the place, flag-bearers bent over, struggling to stay upright. Reporter’s transferred wishful thinking?