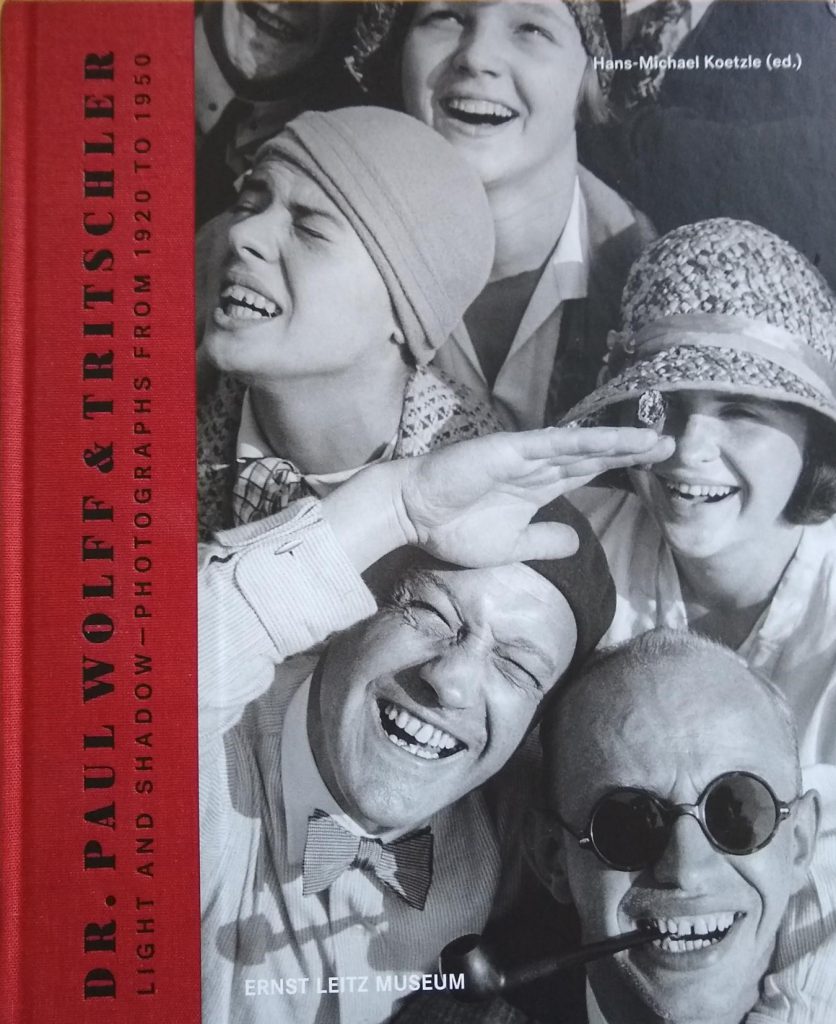

Ernst Leitz Museum Wetzlar Licht und Schatten Fotografien 1920 bis 1950 Dr. Paul Wolff Alfred Tritschler editor Hans-Michael Koetzle Kehrer Verlag

© 2019 Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg Berlin, authors, artists and  photographers [and translator]. ISBN 978-3-86828-881-0

photographers [and translator]. ISBN 978-3-86828-881-0

Ernst Leitz Museum Wetzlar Hans-Michael Koetzle Licht und Schatten Light and Shadow

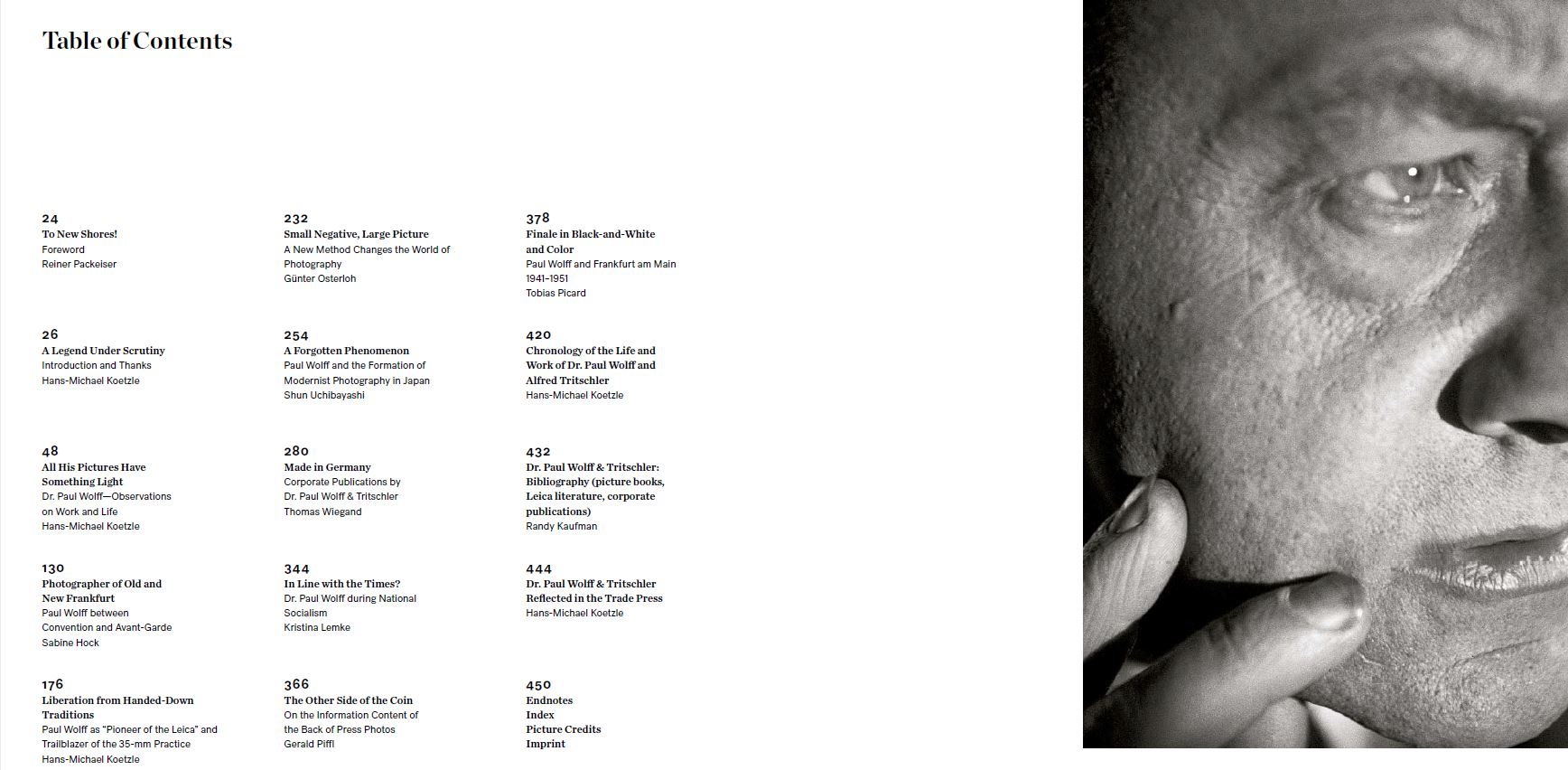

Dr. Paul Wolff & Tritschler. Light and Shadow – Photographs from 1920 to 1950. Published at Kehrer Verlag.

Edited by Hans-Michael Koetzle. Translated from German into English by Alexandra Cox (all contents). Extracts from this substantial publication begin here with selected paragraphs from “All His Pictures Have Something Light”, by Hans-Michael Koetzle. The respective word count in the book is indicated for each essay (for reasons of concision, I omit the endnotes, but they are included in the word count).

All His Pictures Have Something Light

Dr. Paul Wolff – Observations on Work and Life

by Hans-Michael Koetzle. Translated from German by Alexandra Cox.

30,063 words

He was a star in his time. Paul Wolff himself flirted with the term, and a star is what he probably felt himself to be, too. One thing remains undisputed: In the 30s of the 20th century, the photographer, who was born in Mulhouse in Alsace in 1887 and died in Frankfurt am Main in 1951, was an authority, a heavyweight, not only, but above all in the field of 35mm photography, which was regarded with some skepticism at first but was ultimately conveyed to triumph with the considerable assistance of Wolff. By the time his book Meine Erfahrungen mit der Leica was published, Wolff’s name had become inseparably bound to the brand. He was to go down in history as the “Master of the Leica”, with sustained charisma extending right to Japan and the USA. It is virtually impossible to overestimate Wolff’s status as a role model for an army of ambitious Leica amateurs. Taking photographs, writing, handing out advice, he laid waymarkers that continued to be a tangible guide right into the period after the Second World War. “Dr. Paul Wolff – often copied, seldom achieved!” was a commonly cited phrase in those days. Wolff was omnipresent in the printed media. There was practically no German illustrated periodical, no magazine, that would have gone without Wolff photos. With regard to Wolff, Manfred Heiting rightly speaks of a “phenomenon”; in pronouncing this, the publicist and collector had Wolff’s seemingly endless bibliography in mind above all.

At least in the genre’s beginnings, Wolff was also active on the terrain of the documentary film. Any history of more recent color photography is inconceivable without Wolff, while his main interest lay in the print technology aspect of transposing color images. Wolff held highly regarded exhibitions propagating the Leica’s possibilities, in accordance with the motto, “Small negative–large image”. Contemporary witnesses confirm him to have been a lively lecturer—slide shows were still a well-attended, much-discussed major event. We also have evidence of advertising supported by photography. Wolff postcards in black-and-white and color circulated. Especially on the terrain of industrial photography, a field that remains largely overlooked to this day, Wolff set standards in collaboration with his partner Alfred Tritschler. All in all, we are obliged to observe that, for a good two decades, Dr. Paul Wolff was among the most esteemed German photographers: successful, enterprising, even a kind of “brand”—and full of contradictions at the same time.

Further paragraphs from this chapter by Hans-Michael Koetzle of Dr. Paul Wolff & Tritschler. Light and Shadow – Photographs from 1920 to 1950, translated by Alexandra Cox, published at Kehrer Verlag:

Ernst Leitz Museum Light and Shadow Licht und Schatten Dr. Paul Wolff Alfred Tritschler

First Years in Frankfurt am Main

Paul Wolff is quintessentially associated with Frankfurt am Main to this day. While perhaps he had not quite found a new homeland here, he had nevertheless found a new home, following his expulsion from Alsace together with a further 150,000 so-called “Old Germans”. Family ties—relatives of Wolff’s wife lived in Frankfurt am Main—, proximity to Strasbourg, the climate, the medieval face of the Main river metropolis with Old Town and cathedral, may have clinched the issue in advance of setting up home in Frankfurt. In the longer view, the region’s economic strength and its favorable transportation links may have played a role. It was no coincidence that Frankfurt was occasionally referred to as the “secret capital of the Reich” (Alfons Paquet). We will also need to consider Frankfurt’s significance as a trade fair and media city, as a place of important presses and reprographic businesses, such as Englert & Schlosser, H. Bechhold, or the Hauserpresse, with whom Wolff did indeed [again] collaborate later on. At an early stage, the suffix “Frankfurt am Main” became a fixed component of his name, or of his identity as a photographer, respectively.

(…)

Not only was Frankfurt a fixed address from now on—after war and war deployment in France and Russia, and after expulsion and resettlement to a militarily vanquished, politically unstable, and economically ruined Germany. Frankfurt also became Paul Wolff’s first major photographic theme—if you will: in logical continuation of his examination of historical Strasbourg. A considerable number of books bearing a title similar to Alt-Straßburg were published from 1923, initiated, and probably also directed, by Fried Lübbecke, who may have been given the idea by Wolff’s Strasbourg shots to spruce up the media image of the Frankfurt Old Town via comparable, romantically inspired images. “He showed me a few shots of Old Strasbourg,”, Lübbecke recalls in his memoirs, “with a new and artistic look, such as we are not familiar with for Old Frankfurt. Whether he [that is Wolff] could also take [shots] like those for the […] Frankfurt Old Town alliance?” For his early Frankfurt images, Wolff did indeed draw aesthetic links to his Strasbourg cycle, therefore, large plate, a concentrated eye on the architecture, scarce staffage, and an emphasis on the picturesque. The negative sides, “the problematic social and hygienic conditions”, were largely effaced. Only in the late 1920s, and now under the use of the Leica, did the view of Frankfurt become more courageous, the gaze livelier, the perspective bolder.

(…)

If we add Wolff’s occupation with the architecture of Classicism, which began in 1942, then his interest in the city, which has now probably become his own, his examination of its still intact architecture and of a carefree everyday life, spans no fewer than two decades. However, the fact that all this, including the collaboration with Lübbecke, with architects such as Elsaesser or Kramer, or his contribution toward communicating the “New Frankfurt”, finds absolutely no mention in his autobiography is remarkable.

(…)

Click on the poppy below to read more from

Dr. Paul Wolff & Tritschler. Light and Shadow. Publisher Kehrer Verlag. Editor Hans-Michael Koetzle. Translator Alexandra Cox![]()